| bc |

Lorna Hill

by Clarissa Cridland

[ The following is adapted from an article by

Clarissa Cridland published in 'FOLLY' issue 4,

September 1991. Used with the author's permission, with

thanks. ]

Lorna Hill was born in 1902, in

Durham City, England. She was educated at Durham Hill

School for girls and Le Manoir on the shores of Lake

Geneva, Switzerland. This was a finishing school at

Lausanne. Lorna obtained her BA at Durham University,

which is where she met her future husband, a clergyman.

They were married at Newcastle Cathedral and four years

later he was posted to a remote vicarage at Matfen, in

Northumberland. They now had a daughter, Vicki, and Lorna

played the organ on Sundays, ran the Sunday School and

carried out the many duties expected of a country vicar's

wife.

One day when Vicki was about ten,

she appeared with a story her mother had written at

school with a request that Mother write more stories

about 'Marjorie & Co’. Lorna eventually penned

eight books for her daughter, illustrated by herself, and

that was when good fortune arrived in the shape of a

publisher's reader who happened to stay with the family

one weekend. He recommended an agent who sent the books

(as they were, in longhand, with Lorna's watercolour

illustrations) to a publisher, Art and Illustration. The

publisher wrote back, asking that she bring the other

seven books to London but Lorna replied that she couldn't

afford the train fare. They advanced her fifty pounds so

Lorna packed the books into her suitcase and off she

went. A & I typed 'Marjorie & Co for her and

published it in 1948, by which time Lorna had taught

herself to type, two-fingered style. Art and Illustration

went out of business before the final of the initial

eight stories, 'Castle in Northumbria', was published.

Harold Stark, the publisher, took the books with him to

Burke Publishing Co and later accepted the 'Patience'

series.

Flush with funds, the family

attended a performance of Alicia Markova and Anton Dolin

at Newcastle's Theatre Royal. They left, totally

entranced with ballet, Vicki deciding she wanted to be a

dancer. She enrolled at Sadler Wells (now the Royal

Ballet School) in London,. Lorna missed her so much that

she began to write books with a ballet background, the

first being 'A Dream of Sadler's Wells', published by

Evans Bros. Meanwhile, publishers Thomas Nelson, who had

lured Lorna away from Burke, republished the first three

'Marjorie' titles. This caused some confusion with those

published by Burke being called the 'Patience' books,

those by Nelson the 'Marjorie' books.

When both publishers dropped their

Children's series in 1964, Lorna having typed (still

using two fingers) forty books, Evans asked her to write

a biography on dancer Marie Taglioni. This became 'La

Sylphide'. Two adult novels followed from Robert Hale in

1978 but Lorna stopped writing following a couple of

serious operations. She passed away on August 17, 1991,

age 89.

The books in alphabetical order

A Dream of Sadlers Wells (Evans

1950)

Back-Stage (Evans 1960)

Border Peel (Art & Educational 1950)

Castle in Northumbria (Burke1953)

Dancer in Danger (Nelson 1960)

Dancer in the Wings (Nelson 1958)

Dancer on Holiday (Nelson 1962)

Dancer's Luck (Nelson 1955)

Dancing Peel (Nelson 1954)

Dress-Rehearsal (Evans 1959)

Ella at the Wells (Evans 1954)

It Was All Through Patience (Burke 1952)

Jane Leaves the Wells (Evans 1953)

La Sylphide, The Life of Marie Taglioni (Evans

1967) (biography)

Marjorie and Co (Art & Educational 1948)

Masquerade at the Wells (Evans 1952)

More About Mandy (Evans 1963)

No Castanets at the Wells (Evans 1953)

No medals for Guy Nelson (Nelson1962) |

Northern Lights (1999)

Principal Rôle (Evans 1957)

Return to the Wells (Evans 1955)

Rosanna Joins the Wells (Evans 1956)

So Guy Came Too (Burke 1954)

Stolen Holiday (Art & Educational 1948)Swan

Feather (Evans 1958)

The Five Shilling Holiday (Burke 1955)

The Little Dancer (Nelson 1956)

The Other Miss Perkin (Robert Hale 1978)

(romance)

The Scent of Rosemary (Robert Hale 1978)

(romance)

The Secret (Evans 1964)

The Vicarage Children (Evans 1961)

The Vicarage Children in Skye (Evans 1966)

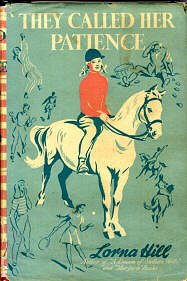

They Called Her Patience (Burke 1951)

Veronica at the Wells (Evans 1951)

Vicki in Venice (Evans 1962) |

For ordering information on GGB

reprints, please go to http://www.rockterrace.demon.co.uk/GGBP

The books in series in reading order:

MARJORIE SERIES

1 Marjorie and Co (Art & Educational 1948)

2 Stolen Holiday (Art & Educational 1948)

3 Border Peel (Art & Educational 1950)

4 Northern Lights (privately pub. 1999)

5 Castle in Northumbria (Burke1953)

6 No medals for Guy Nelson (Nelson1962)

SADLERS WELLS SERIES

1 A Dream of Sadlers Wells (Evans 1950)

2 Veronica at the Wells (Evans 1951)

3 Masquerade at the Wells (Evans 1952)

4 No Castanets at the Wells (Evans 1953)

5 Jane Leaves the Wells (Evans 1953)

6 Ella at the Wells (Evans 1954)

7 Return to the Wells (Evans 1955)

8 Rosanna Joins the Wells (Evans 1956)

9 Principal Rôle (Evans 1957)

10 Swan Feather (Evans 1958)

11 Dress-Rehearsal (Evans 1959)

12 Back-Stage (Evans 1960)

13 Vicki in Venice (Evans 1962)

14 The Secret (Evans 1964)

|

PATIENCE SERIES:

1 They Called Her Patience (Burke 1951)

2 It Was All Through Patience (Burke 1952)

3 So Guy Came Too (Burke 1954)

5 The Five Shilling Holiday (Burke 1955)

DANCING PEEL SERIES

1 Dancing Peel (Nelson 1954)

2 Dancer's Luck (Nelson 1955)

3 The Little Dancer (Nelson 1956)

4 Dancer in the Wings (Nelson 1958)

5 Dancer in Danger (Nelson 1960)

6 Dancer on Holiday (Nelson 1962)

THE VICARAGE CHILDREN SERIES:

1 The Vicarage Children (Evans 1961)

2 More About Mandy (Evans 1963)

3 The Vicarage Children in Skye (Evans 1966)

Adult Books

La Sylphide, The Life of Marie Taglioni (Evans

1967) (biography)

The Scent of Rosemary (Robert Hale 1978)

(romance)

The Other Miss Perkin (Robert Hale 1978)

(romance) |

For ordering information

on GGB reprints, please go to http://www.rockterrace.demon.co.uk/GGBP

Northern

Lights -

publishing history

In September 1997, while visiting Lorna Hill’s

daughter Vicki, we were looking at the original exercise

books in which the Marjorie and Patience stories were

written, when we noticed the words ‘Northern

Lights’ at the front of one of the books, among the

titles written. On enquiring, Vicki explained that this

was an unpublished book by her mother.

Northern Lights is the fourth Marjorie

title, coming after Marjorie and Co, Stolen

Holiday and Border Peel, and before Castle

in Northumbria and No medals for Guy. (Some

readers might be confused by our listing Castle in

Northumbria as a Marjorie book when publishers’

listings in the 1950s and 1960s showed it to be a

Patience book. For various reasons, the publishers were

wrong. There are four Patience books only – They

Called Her Patience, It Was All Through Patience,

So Guy Came Too and The Five Shilling Holiday.)

Northern Lights was written for Vicki’s

Christmas present in 1941, and is Lorna Hill writing at

her very best. The reason why it was never

published before is that it features the war, which the

other Marjorie titles don’t, and by the time a

publisher had seen the books, in the late 1940s, the

British public were apparently tired of books about the

war. So, Northern Lights had languished in the

attic since then. We decided to publish it, and thus

complete Lorna Hill’s publishing opus.

- A & C

Veronica,

Sebastian, Guy and Jane – art,

life, love and landscape

A Personal View of

"The Sadler's Wells" Series

by Jim Mackenzie. [ jmackenzie48@yahoo.com ]

The main virtue of series

literature for the reader is that, once the second or

third book is under way, the territory is familiar and

the boys and girls and men and women are old friends. We

are close enough to the characters to be able to

understand them and relax with them. To a certain extent

we are more deeply involved because we have their

interests at heart. After all, we bought or borrowed this

second book about these people because we liked the

first. We want to see what happens. Naturally this very

familiarity can also become the drawback and the same old

routine can become irritating rather than therapeutic,

intriguing or uplifting. The same repertoire of narrative

tricks, character foibles, closely described settings and

procedures, can be intolerable to both reader and writer.

Perhaps the reader has this effect deadened by the

passage of time, for most series emerge over a period of

years and much other reading intervenes before the next

in the line of sequels is available. The author is

usually afforded no such relief and often returns

immediately to the world which he or she has created. Two

temptations lie ahead: to rely too much on sure and safe

ground, or to try for risky innovation in order to

re-stimulate their own imagination.

I have included this preamble before I turn to a close

examination of Lorna Hill's very popular Sadler's Wells

series because I believe that it is a useful framework

for helping to assess this section of an important

children's writer's output. I hope to approach this task

in a spirit of positive detachment.

"Detachment" because I am male, had never read

any of the series up to three months ago, was neither pro

nor anti ballet as either an art-form or as a topic for

children's literature. "Positive" because last

year I read "Castle in Northumbria" (one of the

"Marjorie" series) and thoroughly enjoyed it.

My own claim to specialist knowledge with regard to Lorna

Hill concerns Newcastle Upon Tyne, Northumberland and the

North-East of England. For instance, I now know that I

attended the same university as Timothy Roebottom (See

"Rosanna Joins the Wells") but he was ten years

before my time. The books were read one after the other

with very little time intervening. Incidentally the

library system of Newcastle Upon Tyne held only four

"Wells" copies, which, I was assured, were

scarcely ever requested. To all intents and purposes

Lorna Hill is an "unknown" author even on her

own native heath. Why should this be so ?

The central characters must always be the first

consideration. Are they interesting ? Do they mature ? Do

they grow ?

The very first book, "A Dream of Sadler's

Wells", begins with a zest that promises well for

the rest of the series. To start in the middle of a

journey with someone in distress immediately engages our

attention and our sympathy. An intriguing meeting with a

self-confident "interesting rather than

good-looking" boy relieves the misery of fourteen

year old Veronica Weston's rail journey north to stay

with her relations in the wilds of Northumberland. All

readers will immediately know that the two young people

are destined to meet again. It's a first-person

narrative, of course, and perhaps the best section of the

whole book, indeed the whole series, occurs in chapters

two and three. I mean it as a compliment when I say that

it is like diluted "Jane Eyre", with the

penniless orphan, Veronica, subject to the whims of the

rather strange Scott family. The younger daughter,

Caroline, is fine, but, aged eleven, has little sway in

family matters. Uncle John is a remote business man who

disappears to his shipping office in Newcastle for most

of this and the subsequent volumes. Aunt June is a snob,

in the early books the worst example of the nouveau

riche, who has very fixed ideas about what Veronica

should and shouldn't do. This is quickly brought out by

her reaction when her strange niece offers to get out of

the Rolls Royce and open the gates for the chauffeur.

"Sit down, dear. Perkins will see to it."

And then there is Fiona, the older daughter. Fiona is

something else again. She is so awful that it is a joy to

read about her. Lorna Hill appears not to have given her

a single redeeming feature. She resents having to share

her room with Veronica and grumbles about the compromises

that people expect her to make.

"There isn't loads of room….I hate having my

things all squashed together."

In fact Fiona's entire conversation appears to be

conducted in snaps and scornful comments. Her comment

about Jonathan's painting of Veronica shows you the

standard style and content of her part in the dialogue.

"Painted you ?" Fiona broke in scornfully.

"Whatever for ? Were you supposed to be a gipsy, or

a child of the gutter, or what ?"

For once we also have a character whose bite is as bad as

her bark. After describing Veronica's only dress as dirty

and "like something the cat's brought in" and

that it made her look like "the dog's dinner",

Fiona snatches it from her and tosses it into the bath

where the colours run and reduce it to a hideous mess.

Having made a bad start in the first story, it would seem

to be difficult for Lorna Hill to make the outwardly

attractive-looking Fiona any worse. However, as the

series unfolds, the spoiled and snobbish child becomes

the wilful and selfish young woman. Her own family having

fallen on hard times, she is prepared to jump ship and

join a family with better monetary prospects. From being

the tyrant of the schoolroom she grows into the mercenary

young woman who can declare as she prepares to get

engaged, "Love doesn't come into it. Love is only

something that you read about in fairy tales." In

fact, everything about Fiona is counter to the prevailing

spirit of the books, the essence of which is that

"Amor vincit omnia" or love conquers everything

– even sometimes artistic ambition. Fiona's

appearance in the first book and her instinctive

selfishness and cruelty are therefore no accident. The

theme of selfishness and selflessness appears in many

guises during the course of the many books. When this is

linked with the concurrent idea of the demands of art

compared with the demands of life Lorna Hill finds her

firmest ground. This theme is sometimes explored through

the parent-child relationship but, given the high number

of orphans in her books, more often through the plots

which show young people growing up and falling in love.

What happens between Sebastian and Veronica is the

cornerstone of the first four volumes in the series. At

first sight, whilst Veronica, the girl whose

determination to reach the top in her chosen art-form and

who has talent to match her aspirations, is the ideal

heroine for young readers, there are many drawbacks to

Sebastian's personality. The world has moved on since the

1950's and many of his statements now appear even more

extreme than they did when they were first written. But

let us go back to the beginning and build up the picture

more carefully and remind ourselves that the narrative in

"A Dream of Sadler's Wells" and "Veronica

at the Wells" is told from the point of view of

Veronica. With the benefit of hindsight we can know that

Veronica marries Sebastian and that it is a happy

marriage. It makes sense, therefore, that any criticism

of Sebastian is withheld. It makes sense that Veronica,

not always the most astute of young ladies, (not

realising the exact depth of the relationship between

Jonathan and Stella, for example) should be unable to put

into words the nature of her love for Sebastian and her

understanding of his quixotic character

The crucial scene is, of course, the one that takes place

in the stable at Bracken Hall just after Veronica has

received the telegram about her first part in a

performance. In the excitement of the moment Veronica has

forgotten all about Sebastian's first concert. Her

imminent departure for London precipitates a crisis and

Sebastian says things that are difficult to forgive and

which appear to mark him down as a thorough male

chauvinist.

"Men are forced to have careers. Women don't have

to; they just barge into them. It's just silly for a

woman to give up everything – friends, beauty sleep,

peace of mind – even marriage – for a stupid

thing like ballet."

Ironically, just as he treats her so badly, he pays her

an elaborate double compliment. She is the inspiration

that has driven him to write the music for the concert

that she must miss.

"How do you know I'm not playing for you, Veronica ?

How do you know I haven't written my Woodland Symphony

especially for you – inspired by your grace, your

funny remote face, the lovely way you move…"

Then he presents her with the second half of the

double-edged compliment, a declaration of love and a

desire to kiss her that had been immediately withdrawn

when she chose to go to London instead of his concert.

Lorna Hill has presented the reader with a picture of a

talented but arrogant young man, confident in his own

talents, used to getting his own way by charm and force

of personality, genuinely in love with Veronica but

living in a world of self-centred expectations.

Veronica's rejoinder to Sebastian

"You're only a kid," I retorted. "We're

both kids."

"I'm almost seventeen," he answered

is also Lorna Hill's timely reminder to her readers that

Sebastian could be forgiven a little for his cruel words

– eventually. He still has a lot to learn.

Sebastian never apologises to her and, indeed, seems to

expect that Veronica is the one that needs to seek

forgiveness. Fortunately for him Veronica, when she has

recovered from the shock and trauma of what happened,

understands. As she waits for her first performance of

Odette-Odile she reacts to the red roses he has sent,

"Just that ! No word of apology or good luck. I gave

a wry smile. How like Sebastian ! He hadn't a big,

generous nature like Jonathan. He was brilliant, and

witty, and arrogant. Above all, he was proud. No, he

would certainly never utter one word of apology to me or

to anyone else – I was quite sure of that."

"No Castanets at the Wells" makes us look at

this relationship again from another direction. It is

another first-person narrative but this time it is told

from the point of view of Caroline, the more sympathetic

of Veronica's two cousins. In heated debate with Fiona,

the hated-one, Caroline tries to explain,

"Because he's a musician, and temperamental. They're

both temperamental," I said, trying to explain,

though I didn't really understand myself. "It may

seem odd to us, but it doesn't mean they don't love each

other." In fact we learn far more about Sebastian's

feelings after we know that he has come to claim Veronica

at the end of "Veronica at the Wells". Through

Caroline's story readers discover the extent of his

devotion and can recognise some stages of his growth. In

their conversation in the roof-garden of a

"well-known London store" he says,

"You're wondering about my quarrel with Veronica. It

was a very long time ago, that quarrel. I'm wiser

now." For a few seconds it looks like he is heading

towards humility but this is followed by,

"I'm not going to apologize to her, if that's what

you mean," said Sebastian, sticking out his chin,

"because I still consider she treated me

shamefully."

However, his instinctive sympathy for Caroline in her own

time of trouble, where he deals with her tenderly and

diplomatically, shows us that he has a heart after all. A

confidence from her brings spontaneously a confidence

from him. Indeed he even confides to her some of his

deepest feelings about Veronica,

"I'll tell you something I wouldn't tell another

living soul….I'm going to become engaged to

Veronica."

And then the key words are said, "- if she'll have

me."

He talks of his first meeting with her "there's been

no one for me but Veronica ever since the very first day

I saw her funny little pale face in the Flying

Scotsman."

Lorna Hill manages to keep his dignity whilst exposing a

more loving side and then, with another narrative trick,

places him back in his enigmatic, half-joking and

half-arrogant character slot once again. The trick in

question is giving Sebastian the last word in Caroline's

tale by making him the narrator of the last section.

Naturally it is told in role and Sebastian reveals few of

his inner feelings apart from his continued dislike of

Fiona and her mother and his capacity for joking humour

that stops just short of a sneer. It would not be

Sebastian if he acknowledged his failings (or his deepest

feelings) or spared anyone from his sarcasm. However,

with a deft touch, the author brings out his love for

Veronica, who at this stage of their lives appears to be

clearly a better person than he will ever be. Her gesture

in kissing Fiona and acting as a peace-maker confirms

what Lorna Hill has been asserting all along,

"Madame says that if your thoughts aren't nice, it

shows in your dancing, just as it does in music or

painting."

This recurring idea is best developed through the

character of Toni Rossini who gives unselfishly to his

partner. Veronica recognises this and says so, "I

don't believe you ever thought of yourself at all."

His reward is to have his own performance transformed by

his generosity of spirit,

"Yet the strange thing was that when he danced as my

partner, people said he was like another person –

that his dancing reached heights that no one believed him

capable of attaining."

Alas for our heroine, Veronica, a moral message is best

delivered, not just through the characters we love to

hate, but also through the suffering and painful

self-realisation of the character that the reader has

been led to like and admire. Lorna Hill is courageous

enough to show that her prima ballerina assoluta also has

feet of clay, albeit this fall from grace is a temporary

one and kept at the sideline of the later stories. Both

she and Sebastian do not reach the end of their story

after three volumes, in spite of their material success

and fame. Nemesis arrives in the shape of Vicki, their

talented, wilful and charming daughter. Briefly Veronica

does an Irma Foster. In other words she refuses to

believe that her daughter can do anything other than

follow in her footsteps. Beneath a sarcastic exterior, no

doubt inherited from her father, Vicki can't bear to

break the heart of her mother and pursue her own dreams.

It is one of the reasons why Jon falls in love with her.

Events are brought to a climax in "Dress

Rehearsal" where Vicki presents Nona as her

replacement,

"Will you adopt Nona, and let her do all the things

you have dreamed up for me ?"

Strangely enough it is Sebastian who shows perception and

sympathy before Veronica,

"Fathers sometimes understand their daughters better

than mothers do."

Veronica herself is prepared to confess,

"I've been thinking lately that perhaps I've been

too much Veronica Weston, and not enough Mrs. Scott !

Someone told me that my only daughter was often

lonely…"

When Vicki tries to find excuses for her parents,

"Oh, Mama – not self-centred !" exclaimed

Vicki, horrified. "Let's say single-minded."

it is Sebastian who insists upon the truth,

"Which is a more polite way of saying the same thing

!"

"Dress Rehearsal" is the eleventh in the

Sadler's Wells series and yet Lorna Hill is still finding

ways in which to show that learning is a life-long

process. The series has been launched well and we can

already see that Lorna Hill can use these central

characters as yardsticks for the future behaviour of the

succeeding heroines and heroes. Veronica and Sebastian

may be kept on the periphery of the action but they still

serve a useful purpose and the reader is still interested

in their fate. Such are the essentials of a series

format.

And yet I fear there is no blinking the fact that after

the first five books the series falls away in standard.

By the sixth book the reader is deeply integrated into

the habits, manners and mores of two communities : the

world of the north-east of England and the world of

Sadler's Wells. But by the sixth book the reader has

begun to realise that the heroines are like runners in a

relay race, passing the baton of artistic striving from

one generation to the next or falling by the wayside:

from Veronica to Jane to Ella to Rosanna to Sylvia to

Nona. By the sixth book the reader will realise that a

young man will come along and that the girl will have to

make a choice. What supports the reader through the rest

of the books is the tapestry of familiar people and

familiar places that has already been woven and which can

act as a backdrop to the increasingly familiar

story-lines. They really are old friends and old

acquaintances and, in some cases, like that of Nigel and

Fiona, old enemies. However, by the seventh book,

"Rosanna Joins the Wells", the author has lost

her instinctive grip over the power of narrative. It was

already slipping somewhat in "Ella at the

Wells" which was her second "Wells"

venture into third person perspective. But, before I

identify what I consider to be the short-comings, let me

outline more clearly what was achieved in the opening

quartet and comment in some detail on what was perhaps

the peak of her achievement in the controversial

"Jane Leaves the Wells".

As has already been said, the first two books offer us

Veronica's perspective on the world. Lorna Hill stays

resolutely inside the character and there are no

authorial comments. We experience at first-hand the

struggles, the cruelties, the joy of success and the

pangs of love. Lorna Hill even manages to convince us of

the love of the countryside that transforms both

Veronica's attitude to Northumberland and her capacity

for bringing feeling to her dancing roles. Choosing to

move the next stage of the story through Caroline's

narrative in "No Castanets at the Wells" was

also a tremendous idea. Caroline's struggles as she comes

to terms with her failure at the Wells are interesting in

themselves but the insight given into Sebastian, Veronica

and Fiona deepens our understanding of their characters

in a part of the story that we already know. Sebastian's

post-script where he "finishes the story" is

another daring attempt to use the narrative form in an

interesting way. The twin narratives of Jane and Mariella

who swop their lives extends this innovative approach to

storytelling into "Masquerade at the Wells".

Jane's story of her transformation from the bullied

victim to splendid success at the Wells heavily outweighs

Mariella's contribution of course. Yet Mariella's

"finishing" of the story of Jane's success is

also a prelude to a more detailed account of her own

story in "Jane Leaves the Wells" where Lorna

Hill resorts successfully to the third person narrative

for the first time. What makes "Jane Leaves the

Wells" such a success, in spite of the missing inner

perspective, is a combination of both a judicious

selection of content and the way in which the author

conveys a tremendous sense of place. Nevertheless, in a

way, with the exception of a few minor developments, this

book really completes all that Lorna Hill has got to say

about the conflicting demands of ballet and of love. The

rest of the series would seem to be outings with old

friends going to familiar places no matter how much she

tries to push unconvincingly into the world of the slums

or the palaces.

To return to "Jane Leaves the Wells", it is

quite clear that Mariella left the Wells in the previous

book. Her affection for the rural life which for a while

is bound up with her infatuation with Nigel is subtly

contrasted with Jane's total absorption in the ballet and

the appeal of her dancing partner Josef Linsk. That both

the heroines are vulnerable to the outward charm of

basically selfish people is placed constantly before the

reader. There are other ironies as well. Mariella sees

clearly what Josef is like and Jane knows only too well

what a hateful person Nigel can be. The other contrasts

lie in their surroundings, and here we can see clearly

this author's ability to both evoke environments and

integrate their special quality into the events so that

they are more than mere landscapes and become at times of

symbolic importance. Though, to a certain extent, Lorna

Hill creates a special feeling of place in each of her

Wells novels (Who could forget the particular place that

the lake in the grounds of Bracken Hall holds in the

hearts of Sebastian, Veronica and Caroline ?) the

landscapes and the people in "Jane Leaves the

Wells" are particularly well-drawn and are worthy of

a closer examination and contain in effect the essence of

the whole book.

Mariella's love of the countryside is not merely a stated

thing. It is explored constantly by reference to her

reaction to the beauty that surrounds her. The

description of the new schoolteacher's cottage with its

square of grass and its rigid lines of lobelia reflecting

the unbending attitude of Miss Goodall, is contrasted

with Mariella's memory of the cottage as it used to be

– a riot of colours and shapes.

"The house certainly hadn't been tidy then. In fact,

it had been nearly hidden under masses of rambler roses,

virginia creeper and ivy. A clematis, with purple flowers

the size of plates, sprawled over the porch, and flowers

of all colours shapes and sizes jostled each other in

untidy flower-beds, and nodded in at all the

windows."

The "perfect lines" so striven after in ballet

and achieved by the domineering schoolmarm now made the

cottage stand "like a policeman, directing the

traffic." Inside the cottage of Mariella's memory

there had been the mixture of the beautiful and the

tasteless that makes up real life.

"Inside there were flowers everywhere: roses in the

front room, spilling out of a hideous china vase with

"A Present from Blackpool" on it, lupins in a

cracked water-jug in the tiny hall, and jam jars filled

with buttercups all over the kitchen."

A laburnum tree which had stood near the gate was

ruthlessly cut down by Mrs. Goodall's jobbing gardener

but remained in Mariella's mind as "a huge golden

umbrella."

This long description is used by the author to

re-establish Mariella's sensitivity and is then followed

by one of a series of seasonal pictures of Northumberland

that place her on harmony with the landscape.

"She rode slowly up the road. It was very quiet. The

long rides of the fir-wood to her left were filled with

deep blue misty shadows, the cobwebs hung their jewelled

nets on every bush, and tall fronds of bracken on the

north side of the road, where the sun never shone,

sparkled with hoar frost. It was a lovely autumn day,

perfect as only autumn days in Northumberland can be.

There was a wide grass verge to the road, and her horse's

hoofs made no noise on the springy turf. Apart from a

slight creaking of leather as she swayed easily in the

saddle, there wasn't another sound. Even the cushats in

the wood had stopped cooing, now that autumn had

come."

It is a picture of Mariella at one with the sights,

sounds and textures of the landscape. In the words of the

old hymn, "Where every prospect pleases and only man

is vile." As if on cue, Nigel arrives and splits the

almost perfect silence with his "View Halloo".

On re-reading the book one is struck constantly by the

number of pictures we are given of Mariella at home with

the landscape and with the people of this large border

county : Mariella waiting in vain for Nigel in the

country inn, Mariella in the village post-office,

Mariella feeding Lady Monkhouse's hens, Mariella setting

off to visit the old lady who lives in the old cottage up

on the moors, Mariella at the fox-hunt, Mariella at the

gymkhana, Mariella sharing with Veronica their delight in

their natural environment…

"Oh, look at the lake ! Isn't it beautiful in the

winter sunshine, and the frost sparkling on the fir trees

? You're right, Mariella, nowhere could be quite as

beautiful as this."

But Mariella's problem is that Nigel too has a

superficial beauty that holds her affections in spite of

the many imperfections of his character. Moreover

Mariella's own beauty of appearance and goodness of

character (constantly both explicitly stated and

plausibily demonstrated) are either ignored or abused.

Lorna Hill will not resolve Mariella's problem in this

volume of the series – her heroine is not yet ready

to see that beauty lies in the crags of character as well

as in the surface smoothness of a man who possesses a

figure like "a Greek god."

Lorna Hill's creation of Jane's world at the ballet is

done differently. The book begins in the middle of a

dialogue between the female members of the corps de

ballet and Jane who has become one of the principal

dancers. Long term reflections on the life of the dancer

are mingled with both kind and cruel comments about their

fellow artistes and mundane matters such as eating,

drinking and boyfriends. Jane's transformation from the

young girl suffering from a cold to the fairytale

princess shows her dedication to her art and this is

certainly what strikes the reader on first perusal.

However, a second look suggests another line of thought

and it is the rather surprising one of artificiality and

not art. From, "Look out, Daphne ! You know you're

not supposed to sit in Carabosse's carriage, even if it

is only an old soap-box !" to the description of

Josef – "He was a consummate artist at make-up,

was Josef, and he had taken good care to accentuate his

best features – his glittering dark eyes, and his

thinly bridged nose with the sensitively curving

nostrils." Lorna Hill is making it clear that it is

a world riddled with falsity and pretence.

Take also Jane's mistake about which reporter was Mrs.

Coggan's son and we can see the whole idea of the

superficial and the true being pursued indirectly. When

Jane insists upon "ordinary" potatoes and a

straightforward peach and Lorna Hill talks of her

"shedding her own personality and becoming a

fairy-tale princess" there are signs being planted

that the world of ballet is not her ultimate destiny. The

fad for fashion which the author explores in the next

chapter leads to the comment, "Yes, ballet dancers

are simple, naïve people" and to the conclusion

that is not meant as a compliment. It is a shame that the

cleverly constructed chapter is spoiled by the clumsy and

"corny" device of having George, the stage-door

keeper, remark in god-like rhetorical tones about the

awful Josef,

"Dance with him, miss, by all means," he

muttered to the empty air. "But don't you go

a-marrying him, that's all ! Don't you go a-doing it !

He's not the right young man for a sweet missie like you

!"

Unfortunately this sort of stage-whisper from the author

to nudge (nay kick) her readers into the right way of

thinking is the sort of thing that starts to dominate the

next few stories in the series.

Much better handled is the scene of reunion with her

parents and Mariella as she returns to the north. Jane's

sensitive perceptiveness is revealed in her thoughts

about Newcastle Central Station.

"Imagine all the meetings and parting that have

taken place on this very platform."

However, there is a new core of self-belief that allows

her to tell her mother just what she thought about the

pony that she was landed with when she was a child. She

is also defiant about the cruelty that is involved in

providing young ladies with fur coats and she stands by

her principles. More than that she is prepared to be

outspoken about her feelings about Nigel when she talks

to Mariella about the projected journey to Scotland. This

is a new Jane who has already embarked upon the path of

character formation and is about to face the more

important journey of actually growing up. Marriage looms.

However, the chosen young man is Guy Charlton . Readers

of Lorna Hill's other books will already know that there

are at least three problems with Guy that complicate the

issue of a straightforward romance. Firstly Guy is almost

perfect – he is kind, considerate, honest, patient

(most of the time) and possesses both immense physical

and moral courage. Should I add that he is rich and

talented, at home with animals both as a consummate rider

and as a caring vet ? Thus he is either too good to be

true or, perhaps, too good for Jane. Secondly there is a

legacy from the "Marjorie" stories that

conflicts with the facts in the "Wells" series.

At one time Guy was clearly destined to partner Esme, and

Lorna Hill's portrayal of their romance is considered to

be one the best parts of those "younger" tales.

It is impossible to dislike Esme and yet now there is

Jane. Finally, inflicting corporal punishment on young

girls who misbehave i.e. a good spanking on the bottom as

in "Castle in Northumbria", must always cause

the reader to stop and think twice about the author's

obvious love for her favourite man.

Even before this unusual romance unfolds, Guy and Jane

are united by their separate memory of a past episode

from Jane's childhood (recorded in "No Castanets at

the Wells") when Guy rescued her from the pig-headed

cruelty that comes to be the hallmark of Nigel's

behaviour. The reader also knows (though Jane doesn't)

from Caroline's account how Guy intervened to stop Fiona

stealing the role of Titania from Jane with her lies to

Lady Blantosh. Guy is fair and honest in all of his

dealings but the author, in spite of the disappearance of

Esme, is showing us that quite early on he had a special

consideration for Jane. In order for the romance to

blossom, Guy has to become a little less sure of himself

and Jane has to gain more in confidence. Above all, they

have got to be ready to obey the underlying principle of

all the Wells books which is that the people who give

generously of themselves are rewarded – even when

the giving consists of allowing the prospective partner

the freedom to escape. By the opening of "Jane

Leaves the Wells" both are ready for a new

relationship and Lorna Hill is very careful in the way

that she handles the details of their gradual union. And

the landscape plays a big part in the way that she does

it. Her first tactic is to move away from the two

familiar territories of the ballet and the Northumbrian

countryside and place the crucial parts of the action in

Scotland.

The precision with which the journey to Scotland is

described makes is possible for any so-inclined reader to

trace the route on the map. Everything in this part of

the book is going to be just right. Unlike the first

person narratives which often remain coy or discrete

about the emergence of feelings and the declaration of

love, this third-person account lays bare every telling

detail. Gradually, on the epic journey in the car through

the snow and the rain, it emerges that both Guy and Jane

are caring and generous people. At every stage of the

trip Guy considers the comfort and good spirits of

Mariella and Jane. In the latter stages Jane

spontaneously offers the fractious Fiona her dance dress.

Other people, including Fiona, Nigel and Josef, behave

churlishly and the affinity of Jane and Guy is thus made

even more clear.

However, the real story belongs to the mountains. The

climbing of Ben Cruachan by Guy and one of the subsidiary

peaks in the range by Jane is not just the physical means

of bringing the two young people together. It is redolent

of hints about the nature of their developing

relationship and of what is to happen to their lives.

Guy's thorough preparations for his day's climbing are

contrasted with Jane's impatient ignorance and

impetuousness. It would be "fun" to meet him at

the top. She sets off ridiculously ill-equipped for the

expedition and inevitably places herself in real peril.

There is a moment before the dangers become apparent when

she feels she has made it to the top.

"Peak after peak appeared for one brief moment, and

then vanished like ghostly giants from another world, and

between them and Jane lay a deep and dangerous gulf that

even she, in her inexperience, knew she could never cross

from this point."

The parallels with her own career in ballet are

irresistible. The gala performance is but the false top

– the minor peak that lies below the achievements of

the likes of Veronica. Oscar Devereux, the wily old

critic, knows that Jane's chance has come too soon and

later the author comments,

"You see, he knew Jane intimately, and he knew that

her character was soft and affectionate, that it lacked

the steel thread that must run through a ballerina's

nature if stardom is to be reached and sustained."

Guy's rescue of Jane has all the ingredients that are

required for the selflessness that is required from a

partner. He surrenders his coat, his gloves, his food

and, perhaps more importantly, a little bit of his old

self some time later as they sit in the safety of his

car. He settles in to deliver one of his usual

tellings-off but is defeated by the affection that he

feels for her. Even his threat of a spanking comes across

as an empty one and, despite her apparently meek

response, his attention has focused on the spirit with

which she extracts a promise from him that they will

climb the mountain together.

Jane has always hated horses and vowed never to ride one

when she gained adult years. When Guy drives to Edinburgh

and reveals that he has booked two mounts for them to

ride her heart sinks in depression and apprehension. Yet,

for the sake of Guy, she forces herself to go through

with the ride. Once again she is prepared to give and, to

her surprise, she suddenly finds that she is the

beneficiary. Guy understands. Guy makes sure that it will

be alright. He believes that he is introducing her into

her natural heritage,

"It's such a lovely pastime, and, being a

Northumbrian, you ought to love it !"

The world of ballet falls suddenly away.

"It was when she was changing back into her ordinary

clothes that she realized with a shock of surprise that

for a whole afternoon she had never once thought of the

Wells."

Yet it is too soon to allow her to leave. To turn to Guy

when she is injured and defeated would be to leave the

reader with a poor opinion of her courage and

determination. She is still growing up, still discovering

things about herself and the world of ballet. Her opinion

of Josef Linsk is now clear.

"I only loved his dancing, and was flattered by the

pretty things he said. I know now that he's not nice,

really, and doesn't mean the things he says. He says them

to every girl he meets !"

Earlier in the chapter she had discovered the

unintentional cruelty of the profession she has chosen

when she sees how the audience reacts to Vivien Chator

dancing the part that should have been hers.

"Oh, the flattering, worshipping, fickle audience !

How quick it is to acclaim, and how quick to forget

!"

Even then her essential honesty makes her admit of her

rival, "I believe Vivien Chator is quite a nice

girl."

Guy's warmth in his conversations on the telephone, his

friendliness in coming all the way to Edinburgh just to

see her, and his commitment in actually being prepared to

admit that this was the sole reason for his journey

cannot help but begin to have an affect upon her. This is

special treatment and it is offered not because she is

Jane Foster, the ballerina. Eventually it is clear to

Jane that he really loves her and that his love is worth

having. Even the manner of Guy's proposal shows the care

with which Lorna Hill has constructed this part of the

book. He chose Princes Street because he thought the

noise and confusion would ease the tension for Jane. His

preferred scenario was entirely different but let us

leave that for the moment and deal with his refusal.

"I'm in love with the stage, and with the ballet

!" she declares.

Guy doesn't try to reason with her or persuade her. It

would be like trying to imprison a butterfly. He offers

to wait if she ever changes her mind and declares that he

understands. His behaviour is both kind and dignified.

His feelings for her are clear and complete; Jane's

feelings for him are still in turmoil. The confusion is

only exacerbated by her worries about her chances for a

complete recovery from her foot injury and then the

opportunity to take the leading role. Lorna Hill

expresses these feelings through the medium of a dream in

which Jane fears that Guy will not arrive in time to

rescue her from a precipice on Ben Cruachan. She wakes

from the dream and confesses to her Aunt Irma that she

loves Guy dearly.

"But of course it's no use – no use at all

– my loving him. I'm a dancer."

Aunt Irma, the last person to understand Jane's true

nature, merely confirms this view of the priorities of

life.

"When ballet comes in at one's door, love must

perforce fly out at one's window…."

When we consider Irma's earlier treatment of Mariella,

which amounted almost to emotional neglect, the

consequences of which we are reminded again in the very

next chapter, you realise that she is the last person

Jane should choose as a confidante. Her views should

carry little weight in the eyes of the readers. However,

from the point of view of dramatic tension, they help to

illustrate the conflicting forces now pulling at Jane.

Even Veronica's indisposition so that Jane gets her

unexpected chance for stardom is not due to ill health or

injury but to another interesting conquest of life over

art that is cleverly used to echo the main story. The

dedicated, divine and unmatchable Veronica is having a

baby and Jane comments that her performance in rehearsal

was more than usually inspired. In the end, however,

Veronica's place must be taken by Jane so that her

destiny can be fulfilled in more ways than one. The

glitter of Sadler's Wells is about to be at its

brightest.

Nevertheless, suddenly the author switches the story back

to Northumberland and Mariella's continuing problems with

Nigel. Amidst the details of his selfishness and her

yearning for some return of the love she feels, Mariella

muses on what has happened to Jane. In view of her own

unhappiness, her conclusions on Jane's success are worth

recording,

"All the same," thought Mariella, cantering

smoothly along the grass verge of the country road,

"I'd rather be up here in Northumberland where it's

quiet, and yes, sane – where there are real things

to do, like riding, and planting out the wall-flowers,

and learning how to cure sick animals. Less glamorous,

perhaps, but more satisfying !"

The description of Jane's gala performance is carefully

constructed so that all the underlying themes of the book

are brought into focus for one last time. The description

of the audience in its glamour and beauty and the

reminder that the occasion is enhanced by the presence of

royalty apparently begins to encourage us in to the

belief that this is Jane's destiny. Her performance as

Odette and the way she conquers the people in the theatre

continues this feeling. Then Oscar Devereux's deflating

comments on her Odile demonstrate that her success is

partly illusion.

"To be brutal it was insipid. She did not fill the

stage."

Jane herself has begun to find the whole occasion unreal.

There was a "dream-like quality" about it all

and she couldn't believe that it really Jane Foster who

has performed. What comes to her mind is Guy's face and

what comes to her heart is "a little ache in her

heart that surely ought not to be there."

Lorna Hill takes care to let us know that the audience

are no longer beautiful – they are "lavishly

dressed". They may be enthusiastic and charmed but

they are not "knowledgeable". Jane's mind

dwells not on her triumph but the distressing words that

she had heard after rehearsal that very afternoon. In the

opinion of her peers, her fellow dancers, she was

"adequate, but just not top grade, and never will

be." Her vision of the future if she stays within

the world of ballet is revealed to be both tawdry and

slightly preposterous and culminates in an image of the

once handsome Josef covering his baldness with a wig.

As Jane puts it to herself, "She was on the top of

the highest peak.." but just like her adventure on

the lower hills of the range by Loch Awe she realises

there were still other mountains that she could not

climb. The understanding is that, in contrast, Veronica

touched the stars. It is better to have a world where you

can keep on climbing and not one where you are "over

the hill".

This takes us back to Guy's proposal in Princes Street

and what he would have said if they had been ready to

dedicate themselves to each other. What he wanted was

that their declaration and commitment to each other

should take place on the top of Ben Cruachan so that

their "promise would be solemn and binding, made, as

it was, in the very heart of the hills." When she

sends her telegram it means that Guy and Jane will climb

Ben Cruachan together and it will be a symbol of how they

will approach their future life together. The country

that lies ahead is challenging but also real and

permanent. His love as yet may be stronger than hers but

the book has shown us that she has courage and

determination as well as a "soft and

affectionate" character.

It is this reader's opinion that Lorna Hill was never

herself to reach such heights again. There are many

virtues in the remaining stories and there are many

"old friends" amongst the characters and some

charming new ones yet to meet but never again does she

catch so well her characters at the point of ripening

into adulthood and self-realisation, nor does she present

as successfully the conflicting demands of art and human

love. From now on some of the backgrounds jar – the

Ruritanian world of Leopold and his pursuit of Ella is

demonstrably false and the unrelieved awfulness of the

lower classes as depicted in her vision of the mining

village of Blackheath smacks of snobbery. They were

attempts at innovation but her realisation of the details

lacks the conviction that she brings to the milieu with

which she was most at home – the doings of the rural

gentry and the middle class. And occasionally the plots

falter so that the readers are given the sudden

telescoping of years of life so that summary takes the

place of effective scene depiction. Also, depressingly,

there is the outrageous padding of "Return to the

Wells" when overwhelming details of the Swiss

countryside add little or nothing to the emotional

validity of the action. How unlike the careful

integration of characters, action and setting that we

have seen in "Jane Leaves the Wells" ! Worst of

all, perhaps, is the feeling that Lorna Hill, in spite of

her forays into the world of kings and princesses, is now

playing safe. Again and again you are met by reassurances

that one day the heroine will be in the midst of success.

You long for an editor that would have told her to let

the readers find out for themselves and one that would

have been bold enough to ensure that the titles in the

middle of the series did not give away the eventual

conclusion - such as happens with "Rosanna Joins the

Wells."

The quality of the first five books sustains the whole

series. The reader is hooked and, in spite of my

reservations, there are still some gems to be uncovered

in the later books – Vicki's journey with Nona, the

awful attack on Sylvia, the discomfort of nasty Nigel and

many others. And, if you enjoyed the Wells series, there

are still two further directions you can travel with this

author. The "Dancing Peel" series will take

back to the world of ballet and the "Marjorie"

and "Patience" series will return you to the

world of children. I have no hesitation in saying that I

prefer the latter alternative. #

Castle in Northumbria

Reviewed by Jim

Mackenzie [ jmackenzie48@yahoo.com ]

Just what is the essence

of a writer's appeal, the magic that draws the readers

into the world of fiction, holds them there for a while,

and then releases them back into the real world

entertained, diverted and sometimes uplifted ? Which is

it – plot? characters ? setting ? theme ? What makes

a good children's book ? When it comes to a children's

series what are the ingredients that sustain you through

the different stories, through the good plots and the

bad, that make you want to find out what happens next ?

How can a writer use the assets of familiarity,

inevitable in a series, and offset them against the

drawbacks of repetition and the improbability of further

adventures ? Most of us eventually realise that we are

all entitled to one great adventure in our life: growing

up, leaving home, falling in love, marriage, having

children, but how can we, even as young readers, tolerate

so many incidents happening to the same select group ? Is

it because we want them to happen ?

It is thus in a spirit of

honest enquiry that I look more closely at "Castle

in Northumbria" by Lorna Hill, an author whose

popularity appears to be again on the increase. At the

time of writing this article it is the only book by this

author that I have read and so all my deductions and

evidence are drawn from this text. Doubtless there will

be Lorna Hill experts who can tell me more. I look

forward to hearing from them.

Let's start with first

principles: I enjoyed this book. As I am neither young

nor female then I am going to presume that there are

factors in the book that depend neither on the naivety

nor the gender of the reader. "Castle in

Northumbria" is clearly one in a series as

references are freely made to other adventures in other

places. I hope to read them some day and I certainly

could consult a bibliography, but that is not the point

of this particular exercise. Let it stand on its own

merits.

It is definitely a lost

world, an age of innocence that can never come back. The

boys in this story range from a twelve year old, Toby, to

Guy, who is nearly sixteen. The girls in the story are

nearly all fourteen and the friendships and relationships

between the sexes depicted here just could not happen any

more. I seriously doubt if they could have done at the

time (early 1950's). However, as we shall discover, that

is really a part of the fascination of the book. There is

also a strong class perspective with most of the

participants belonging to public schools and being pretty

well off. (They each own their own pony and a chauffeur

drives them to their camp at the castle.) There is a

clear line of demarcation between these children and the

people of the village, though, to be fair to the author,

her central characters nearly always behave impeccably

and are rarely patronising. Any one who is

"stuck-up" is usually given very short shrift

by the others.

Anyway, to start with the

plot - nothing much happens but, in some ways, everything

happens. There are no hidden passages, no dastardly

villains, no natural disasters, no sudden revelations, no

arduous journeys, no real moments of self-discovery, and,

in this book at least, no falling in or out of love. It

reminds me of the comment of the Scottish lady who went

to see a Chekov play, "There wasn't much action but

I do feel I know everyone so much better."

|

Judith,

wearing Marjorie's dress. She is about to be the

May Queen. |

|

Pansy,

the narrator of the story. |

Basically, to sum it

all up, five children go away camping during the Easter

holidays under the walls of an old castle in

Northumberland and they meet two other girls of differing

personalities with whom they interact in both a positive

and negative fashion. The children quarrel with each

other, forgive each other, ride their ponies, get soaked

in a night-time storm and witness a May Queen procession.

It sounds a pretty tame string of events, doesn't it ?

However, I have missed two vital ingredients: firstly the

almost entire absence of important grown-up characters

and, secondly, the ebb and flow of feelings that surround

Marjorie and her uneasy relationship with Guy. In fact it

would be possible to identify a line of development that

tracks Marjorie's misbehaviour and how Guy attempts to

deal with it. And herein lies one of the strengths of the

book – the plot does not strain the reader's

credulity with the usual time-worn devices of children's

adventures. Lorna Hill concentrates on the interplay

between the characters of the children and does not look

outward for artificial excitements.

Yes, it's the characters

that matter. Surely the only worthwhile test of the

personalities of the children is whether we want to meet

them again as old friends in the next book in the series.

And it is Marjorie who matters the most for she is the

problem child. She is vain; she is foolish; she can be

cruel and she is certainly selfish. Yet the other

children still seem to like her and remain friends with

her to the end. Even Guy, her greatest adversary, doesn't

want her to go back to school still carrying a grudge for

the way in which he has treated her. Marjorie is the fly

in the ointment, the spanner in the works, the creator of

tension and unpleasantness, the one who sets the reader's

teeth on edge. She is the tempted one in the Garden of

Eden. In contrast Guy is almost infuriatingly God-like.

His well of common-sense is never plumbed, his patience

is almost of Job proportions, his determination is

rock-solid, his courage undoubted and his punishments

swift, brutal and fair. His forgiveness and kindness are

also clearly to be seen. He is almost a model young man.

On a second reading of the book I was pleased to find a

few faults with him. In particular his persecution of the

tender-hearted Esme over her use of American and slang

terms is revealed to be arbitrary, for he finds it

acceptable for boys to use them. He also comes across as

a bit of a bully – in the nicest possible way.

Now we had better deal

with the part of the book that would be the strangest and

most unacceptable to a modern audience. When Marjorie is

revealed as a liar who had no real permission to be on

the holiday, when she shows her cruel streak by swishing

poor Thomas' pony with a hazel switch, when she stays out

all night, leaving the others what amounts to a suicide

note, when she wants to disappear on a date to the cinema

in Hexham to see an unsuitable film with an unsuitable

young man, it seems reasonably fair that she should be

punished. What is unexpected is that Guy's punishment is

to put her over his knee and give her bottom a good

spanking with his rubber-soled sand-shoes ! Remember she

is fourteen and he is only nearly sixteen. However,

"The spanking really did seem to have improved

Marjorie, or at any rate to have subdued her, and she

managed to behave quite decently."

In the context of the book Marjorie can eventually

forgive the humiliation of her treatment because of her

greater need to belong to the Clan, as the children have

styled themselves. Already the theme of the book is

intruding into this account without my meaning it to.

It's best illustrated through the character of Pan. Pan

(or Pansy Pierce) is the narrator of the story and a

pretty self-effacing one at that. It is another part of

the fascination of the book that you don't notice this

important personality who shapes our view of events until

you take a second look. However, the childish game of

Fugs and Tecs at the Thankless house suddenly sharpens

our perspective on both the character herself and the

morality by which the children are endeavouring to live.

Lorna Hill allows us to see how Pan is affected by both

compassionate justice and the workings of her conscience.

Pan's crime is two-fold.

She strays into a part of the house that has been put out

of bounds and then she lies about why she did so. The

incident soon passes off amongst other events, but not

for Pan:

"The lie I had told weighed heavily on my

conscience, so much so that it cast a cloud on everything

– even the tea."

She confesses her sin. She tries to explain her feelings

about being hunted and how it amounts to almost a phobia.

The splendid Esme is soon ready to forgive Pan but by now

the reader knows that it is Guy's opinion that matters.

"Well, you realise, I suppose, that you've let

the Clan down," Guy said slowly, but his voice

didn't sound nearly so cold. "Broken two of its most

important rules – told a lie and disobeyed orders.

You'll have to atone for that, you know."

Pan longs for punishment, for after punishment it will be

over. The others decide that she must wash all the supper

things and remain silent all during the meal. It doesn't

sound particularly hard but Lorna Hill suddenly

illustrates the deep friendship of the community of

friends by the behaviour of the others.

"When I had cleared away the supper things and

had taken them over to the trough where we usually washed

up, I found that there weren't so very many after all.

Esme had made one plate do instead of the usual two, and

so had Guy, whilst Tony stirred his tea with his penknife

so that I hadn't his spoon to wash, and his saucer was

clean. My heart swelled in gratitude to them all."

Later the children visit the village church and look at

the Beatitudes that were written on the walls. Guy picks

out "Blessed are the peacemakers" and makes Pan

blush furiously by saying that he thought of her when he

read that for he had noticed the way she butted in

between him and Marjorie when they looked like fighting.

The sayings are then turned into a joke by Marjorie for

she realises that neither she nor Guy could ever be

blessed as meek. The point about worthwhile behaviour is

made but not laboured.

Esme too breaks the rules,

putting her life into danger by climbing on the walls of

the castle. Again Guy attempts to sit in judgement but is

confounded when he hears Esme's reasons for her dangerous

venture and he finds himself apologising to her.

"I'm awfully sorry I was cross, Esme. As Pan

says, I was scared to death. Please forgive me and dry

up."

So, inevitably, the theme of the book is friendship and

the values and feelings that underpin it. In spite of the

quoted episodes Pan and Esme are already kind and

basically selfless individuals. Their lapses from the

high standards of the Clan (in each case for very

understandable reasons) make them likeable and credible

characters but less effective as examples than Marjorie.

Her transgressions are vivid and memorable. Lorna Hill

creates some magic moments. Take the time when Marjorie

plucks the new party dress she has been sent by her Aunt

Ursula out of the box and throws it onto the grass. Guy

confronts her.

"You pick it up or –"

"All right !" Marjorie exclaimed. "I will

pick it up." She seized the bread knife – the

one really sharp knife we possessed, barring the boys'

scout knives – swooped down upon the frock, tossed

it into the air, and caught it upon the blade as it came

down. There was a rending hiss as the knife slit through

the silk stuff."

"Yippee !" she yelled, waving the frock wildly

round her head. "What price the White Ensign !"

Marjorie's has to atone for her fury by agreeing to lend

her dress to Judith so that she can be May Queen in a

glorious fashion. Guy also later forces her to do the

Latin preparation that she had hoped to avoid by running

away on holiday with them. Justice is done and seen to be

done and in an apposite and interesting manner.

There are also comic

interludes brought out most strongly through the

character of young Toby, who manages to deflate Marjorie

with well-chosen insults and wry comments. At one point

she complains about the midges,

"Gosh ! One's bitten me right on the end of my

nose !"

"Rotten luck !" Toby said. "For the midge,

I mean !"

The writer is also very adroit and amusing in her use of

small details to identify the differing characters of the

three girls. At one point Esme is discovered stirring her

tea with a hoof pick which was used only that morning to

clean Guy's pony's hoofs.

"I don't care," retorted Esme calmly,

continuing with her stirring. "I don't mind one bit.

After all, horses are terribly clean animals, aren't they

? They even smell lovely."

"But their hoofs !" I said with a shudder.

"You don't know what they walk on, Esme."

"I do !" Marjorie exclaimed, "They walk on

–"

"Shut up, Marge !" ordered Guy. "We all

know what you're going to say, you disgusting girl!"

There is a sureness about the long

stretches of dialogue, particularly near the beginning of

the book, so that when the children argue, discuss and

reflect, you begin to know instinctively who is speaking

which line without having to look.

And as for the setting ?

Lorna Hill makes it seem both romantic and down-to-earth

at the same time. Pan's imagination can visualise the

Border warriors of long ago gathering in the castle

courtyard with their hooves clattering on the

cobblestones. Reality of life by the castle walls is

illustrated by the usually all-knowing Guy having chosen

to camp just where the waterspouts of the roofs and walls

dump their outflow whenever a storm breaks. The

excitement of rescuing a tiny lamb from an area of

bog-land is followed by the practical details of how to

get rid of the mud that has stuck to them in the process

of saving it. In the same way the author gives chapter

and verse about the food they buy and the meals that they

cook. The balance between what you want to know and what

you need to know is kept very well. In short, the

descriptions of landscape are brief but effective.

So, fifty years after it

was first written and published, "Castle in

Northumbria" still has, for me at least, qualities

which make it stand the test of time. More than anything

else it is rewarding to find that the characters are so

fresh, lively and engaging. Now let me subject them to

that "worthwhile test" I mentioned earlier.

Would I want to read about them again ? The answer is

"yes", for there are things which have been

left unresolved. For instance, Guy clearly likes all

three girls but will the relationships with any of them

ever go any further ? They don't need to, for a series

may stop where it wants to, but I believe that the reader

does need to be kept wondering. The possibilities need to

be kept open.

And, of course, what will

Marjorie do next ? Has she yet exhausted all the

different ways in which she can be so charmingly

obnoxious ? Will she grow up ? Being caught in the

tension of hoping she will and hoping she won't is

definitely one of the most effective hooks that Lorna

Hill puts into us. At a lower level Enid Blyton achieves

it with her abrasive George/Georgina figure in the first

four "Famous Five Stories"; at the highest

level L.M. Montgomery makes us yearn for the mischievous

Anne of the "Anne of Green Gables" story even

while we celebrate her maturity in her proposed union

with Gilbert at the end of "Anne of the

Island". The sense of Pan, the sensibility of Esme,

the loneliness of Judith, the snobbery of Sylvia Wade and

especially the sheer effrontery of Marjorie and the

domineering "rightness" of Guy are all

definitely worthy of another outing. #

COMMENTS

11/08/2010

Having read a review on the book I'm currently reading - Castle in Northumbria - I realised it's going to be very similar to the only other Lorna Hill I've read - It Was Through Patience. Both books are about children camping, both written in the first person, both have each child owning or having access to, a pony, all families have a chauffeur, and though I haven't reached the bits yet, both have children camping who have been expressly told by parents not to, and both have a girl going to the cinema to see a film she has been told not to. I thought Enid Blyton had a reputation for repetition, but I think these 2 Lorna Hills really take the biscuit.

Sarah

Back to Collecting

Books & Magazines home page

For ordering information on GGB

reprints, please go to http://www.ggbp.co.uk/

bc

|

bc |