| Bannermere and the places from

the mind of Geoffrey Trease.

Just ONE

page on the Collecting Books and Magazines web site based in Australia.

Jim Mackenzie writes of Geoffrey

Trease's Bannermere series of books.

The Books, the

Places and the People.

Geoffrey Trease

Society

|

The

World of Bannermere –

The PlacesIn the second volume

of his autobiography "Laughter at the

Door" Geoffrey Trease declares quite clearly

that

"Bannerdale, with its lake and forbidden

islet and its sombre mountain Black Banner

lowering over it, is one of those private fantasy

regions that authors, and especially children's

authors, love to create."

However, nowadays it is not at all easy to get

hold of "Laughter at the Door", and the

story of the creation of Bannermere is worth

telling again here so that everyone can share in

what emerges from his personal record of how he

created the place and the people who populated

it.

As we shall see, Geoffrey Trease confirms his

own description of the author's need to have a

"magpie mind", the sort that garners

information from a multitude of sources. Each

detail gradually filters through the brain until

it emerges some time later when he finally needs

to use it. Some of the specific Bannermere

influences we can try to draw together here.

|

In 1940, whilst still waiting for his call-up into the

armed forces, Trease discovered that the meagre flow of

money he was earning from writing was starting to dry up.

He had a wife and a young daughter to support and so

economic necessity drove him to apply for a job as a

schoolmaster in a preparatory school on the seaward side

of the Lake District. It was at Gosforth, three miles

inland from Seascale which is on the coastal railway

route travelled so often by Bill and Penny in the

Bannermere stories. In fact Trease recalls how each

journey north afterwards gave him a "temporary

lifting of the heart" as he looked to the fells on

one side and across the Irish Sea on the other. He became

attuned to the rugged beauty of the place and, as he

walked the hillsides and explored lonely valleys, he

developed that feeling for its special inspiration which

never really left him.

However, it could never really be a permanent feeling

of happiness or content for the people that mattered most

to him, his wife and young daughter, were back in

Abingdon. The countryside was wonderful but the

loneliness was almost overpowering. There was also the

feeling of the world falling to pieces as Hitler's grip

on continental Europe began to turn into a stranglehold.

Then we must also consider the much more personal worry

about whether to send his daughter to Canada, the U.S.A.

or even Australia to be safe from the Luftwaffe's bombs.

"The tension in our lives derived not from

what WAS happening but from what MIGHT. The imagination

could function as actively amid the deceptive quiet of

the fells as anywhere else in the country."

When his call-up finally came it was to Carlisle that

he was required to report. He found himself in a hut with

ordinary men from all over Cumberland and Lancashire. He

conveys very piquantly the indignity of being stripped of

all his individuality and, as he watches his civilian

clothing being stuffed into a sandbag in order to be sent

home, he comments balefully :

"I felt halfway already to being a name on a war

memorial."

Yet for a writer who is accustomed to soaking up

impressions like blotting paper does ink it gave him a

golden opportunity. He sums it up as an "enlarging

experience" and comments that

"Shakespeare could have drawn those camp-fire

groups on the eve of Agincourt from the men in my squad."

I have purposely included this brief early section of

his long wartime service because he declares that this

knowledge of the ordinary working countryman allowed him

twelve years later to create the character of "Willy

the Waller", whose troubles are the mainspring of

"Black Banner Abroad".

And yet it is not until 1947 that we come to the key

moment where all the distilled experiences of Cumberland

and Cumbrians finally produce the spur to write "No

Boats on Bannermere" and its four sequels.

It was while he was in west Cumberland on a long

lecture journey that he came to the small town of Millom.

At the end of his afternoon lecture two girls asked why

he didn't write school stories. They made it clear that

they didn't want "midnight feasts in the dorm,

secret passages and hooded figures".

Instead they required "true-to-life stories,

about real boys and girls, going to day-schools as nearly

everybody else did?"

That short conversation became a challenge and then a

year or so later turned into "No Boats on

Bannermere".

And now for some of the facts that Trease reveals

about the Bannerdale places.

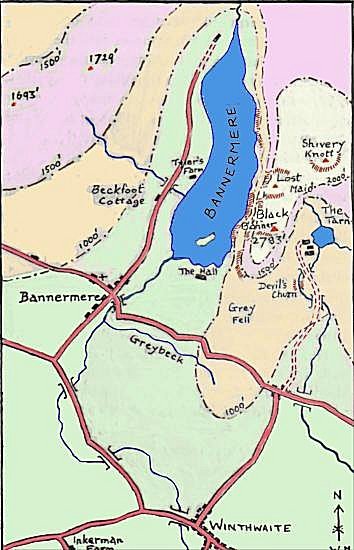

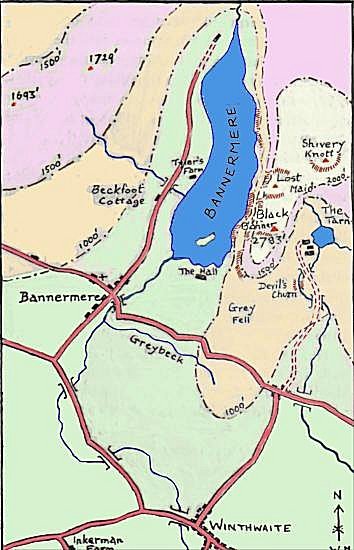

First of all he makes it clear that though there is a

real Banner Dale just east of Saddleback and there are

Bannerdale Crags ranged above it, they have nothing to do

with his Bannerdale. In fact he has never even seen that

place. His Bannerdale is a combination of both Wasdale

and Eskdale with other features drafted in from

elsewhere. The jaws of Borrowdale, for example, are the

inspiration for the Gates of Bannerdale. He declares that

Black Banner was suggested by the real mountain Black

Sail. Perhaps most importantly the town of Winthwaite was

based on Cockermouth "shifted southwards for

literary convenience".

Thus the dedicated traveller has a few points of

reference to which he or she can make his or her

pilgrimage. But you will have to be very careful. There's

no station in Cockermouth at which you can arrive in the

rain. Perhaps it's still possible to search the streets

for Botley's in order to request the splendid cakes or

the ice-cream that makes Bill's eyes pop out (or was that

the first sight of Penny ?) It would be nice to find the

sports ground almost ringed by the hills but still

allowing a glimpse of the distant Isle of Man and imagine

again Bill's fruitless chase round the track after the

nauseating but talented Seymour, or the Kingsford devised

frantic cricket matches resembling the battle of Waterloo

or, best of all, Bill's final rugby encounter before he

too becomes one of the "old boys" of the

school. Is there a shop in Cockermouth which would do for

Mr. Morchard's booksellers and is the public library

still full of old fossils who would leap out of the

shadows to screech "Silence"?

But I am forgetting that this is an

"invented" world. In the town which produced

William Wordsworth there seems little danger that we can

ever establish a plausible "Geoffrey Trease"

trail ! I would much rather have the world of the books,

the world which has been made vivid and memorable not

just by the clarity and loving care of the author's prose

but also by the skilfully executed maps where every

detail of the adventures can be faithfully traced. I can

still remember arguing with a class of 11 year olds about

the exact place where Miss Florey meets Sir Alfred with a

spade and getting them to mark on their own neatly drawn

copies just precisely where they thought the skeletons of

the monks would lie. Just a glimpse of the Black Banner

range with its evocatively named lower peaks of Little

Man, Lost Maid and Shivery Knott is enough to send me

back to the pages where they find the almost lost valley

of Black Banner Tarn. Without being at all unreal it's

better than any reality, and you are forced very happily

to agree with the author as we give him here the last

word about Bannermere. As a one-time schoolboy reader,

one-time English teacher and now writer of rambling

articles about my favourite author, I know what he says

is true.

"Nowadays I can perhaps say, without blatant

immodesty, that it (Bannermere) does not 'exist merely in

my own mind' but exists also in the minds of a lot of

people who, in childhood or later, have read the stories

I laid there." (Geoffrey Trease –

"Laughter at the Door")

Footnote:- The two volumes of Geoffrey Trease's

autobiography "A Whiff of Burnt Boats" and

"Laughter at the Door" whilst not being

commonly available are not impossible to obtain. The

information above merely scratches the surface of what we

learn about the life and work of this superb storyteller

in those two excellent volumes full of his usual

humorous, perceptive, honest and stimulating writing. I

hope the above makes you want to read them.

The World of Bannermere –

The People

The four central characters of the saga grow up during

the course of the five Bannermere/Bannerdale books. Thus

the observations here are confined to general

characteristics so that those who have not read all the

adventures will not have the stories spoiled. Similarly,

to avoid the disappointment of gaining information you

didn't really want to know, I strongly counsel against

reading the article I have entitled "A Fine

Romance", until knowledge of all the books makes you

ready.

William Derek Melbury (Bill)

Bill tells us each of the stories but the last

thing you would call him is an omniscient narrator.

Sometimes you realise that he doesn't really have much of

a clue about what is going on around him, nor a full

appreciation of other people's feelings. That is how

Geoffrey Trease conveys the very essence of what it is

like to grow up – to be a major character in a story

where the reader has the benefit of hindsight and the

broader view long before Bill himself discovers these

things. What strikes you most about him is his decency

and his good humour. Whilst constantly deprecating his

own abilities, he is a talented and appreciative

classical scholar, a dependable friend and (almost

contradicting the previous comments about his lack of

perception) at times a shrewd observer of human nature.

He loves literature, especially plays, and comes to

develop a particular affection for the countryside around

Bannermere. Some of his efforts to become a writer draw

deeply upon Trease's own experiences of struggle and

failure and the need to find an individual artistic

inegrity. We share his setbacks and his triumphs, his

hopes and his fears, not just in his literary endeavours

but also when his other deepest feelings are involved.

Susan Melbury

At one point Bill declares that Susan is a much

nicer person than he is. Though one year younger than her

brother, Susan comes to terms much earlier with what she

wants from the world and the people who are going to be

most important to her. The life of the countryside has an

overwhelming appeal for her and this comes out not just

in her interest in farming but in her knowledge of

wildlife and the local people. Her friendship with Penny

is a deep one and the two of them clearly share many

secrets about their relationships. A part of the fun of

the books is the good-natured bickering and bantering

that takes place between Bill and Susan as they settle in

to Beckfoot Cottage, their life in Bannerdale and their

respective schools in Winthwaite.

Mrs. Melbury

Many critics have made much of the point that Trease

appeared to be breaking new ground when he introduced the

subject of divorce into this series of stories. Bill and

Susan's father is not absent through any of the

traditional stand-by devices of children's literature

– an expedition up the Amazon, managing a farm

somewhere in Africa or killed whilst on active service.

Mrs. Melbury had a husband who deserted her and who went

to Canada. In his narrative Bill is careful to point out

that there are many other children like him and Susan.

However, it is better to remember Mrs. Melbury as an

eminently sensible woman who talks through each decision

that she makes with both of her children. In particular

the episode where she offers to write a letter for Bill

to the mother of an officer who was killed in the war

(Black Banner Abroad) brings out all her best qualities.

Both Tim and Penny soon turn to her as an unofficial

auntie. Susan attributes some of Penny's more foolish

errors to not having a mother like hers. The theme of

loneliness and isolation is also often explored by the

idea of Mrs. Melbury left alone at Beckfoot whilst the

children are at school or involved in some adventure.

Penelope Morchard

Penny's physical appearance is mentioned many times

during the course of each of the novels. Three things are

bound to remain in our memories – her dark hair, the

smooth perfection of her skin and the look of mischief in

her dark eyes. Of course we should also mention her limp,

the result of a childhood accident that has apparently

blighted her life. There are no miracle cures in Trease's

books, at least not ones for physical disabilities.

Penny's route to maturity is the hardest of all the four

children that we meet in "No Boats on

Bannermere". Her talent for acting, her natural

vivacity and her passionate nature cannot always dispel

the feeling of gloom that overwhelms her when she

considers how she might have been a success on the stage.

In some ways her access to all the books in her father's

shop and the lively discussions she has with her

affectionate parent have made her older than her years.

In other ways she is a prey to her sudden enthusiasms

that lead her into foolishness that teaches her the harsh

lessons of this world. Each member of the Melbury family

eventually brings her something she has never had before

in her life but to tell more would spoil the story of the

books.

Tim Darren

Tim's ambition to be a detective is at the core

of his character. He is always sensible and patient in

his approach to all the problems and mysteries that they

encounter. The combination of his deliberate procedural

methods and the sudden insights of Bill and Penny allows

the reader to enjoy every aspect of their adventures. He

represents solid Cumbrian common sense – in

particular we remember the advice he gives Bill and the

others about safe behaviour whilst out on the fells.

Inevitably his slowness and "plodding"

occasionally lays him open to the ridicule of the others.

However, he laughs at himself and confesses that the

police in the district treat him warily because of

previous examples of his misplaced zeal. His future is

mapped out in a plausible and satisfactory manner –

making another contrast with the insecurity that lies

ahead for both Bill and Penny.

Miss Florey

The new headmistress of the local girls' high

school has swept through Winthwaite like a breath of

fresh air. She represents knowledge without

"stuffiness" and is ready to try new methods of

developing the limited opportunities of girls in a remote

Lakeland market town. A formidable scholar herself, she

expects and receives high standards in others. Though

clearly a generation away in age from Penny and Sue, she

understands that the world has changed and that

relationships between boys and girls as they grow up are

not only inevitable but healthy. During each of the books

she shows a great deal of determination and ingenuity in

ensuring that joint activities between the boys' grammar

school and her own establishment should foster the right

kind of social interaction. Very soon she moves from

being merely a headmistress to being a friend of the

family. In particular she wins the undying loyalty of

Penny whom she steers through various scrapes with

patience, firmness and good humour.

Mr. Kingsford

Though the books concentrate on the fortunes of

the four main teenage characters, it is fascinating to

note that the oldest character of all is also subject to

a process of change. In the opening chapters of "No

Boats on Bannermere" he is presented as a

"benighted old fogy". In particular he appears

ruthlessly determined to stamp out any possibility of

friendships between the boys of his school and the young

ladies of Miss Florey's establishment. As the books

proceed we see many other sides to his character, though

what stands out are his courage, his honesty and his care

for the boys in his charge. He is not ashamed to admit

when he has been wrong and he undergoes a complete

"volte-face" with regard to Miss Florey by the

end of the first book. Perhaps the best way of catching

the essence of the man is the chapter in "Under

Black Banner" where he steps in to take a lesson for

a teacher who is absent. His teaching is exciting and

compelling whilst it lasts, and clearly makes a deep

impression on Bill after it is over, for it inspires him

to take on the world of bureaucracy in the cause of the

farm at Black Banner Tarn. The subject matter of the

lesson includes a description of how Kingsford's own aunt

had behaved when fighting for votes as a suffragette. At

the time he had been ashamed of her but now he knows she

was right and he has nothing but admiration. That he

should become reconciled to Miss Florey's changes is thus

entirely plausible.

Johnny Nelson

Bill's admiration and liking for Johnny, a

senior boy at his school, shows that he is becoming a far

more rounded person himself, appreciating the different

qualities that go towards making a worthwhile person. For

Johnny possesses no physical graces and in both

appearance and behaviour reminds Bill of a friendly young

horse. Susan's feelings about Johnny are rather

different. Outstanding at sport and not without ability

in his studies, Johnny is both reserved and shy when it

comes to talking. Even though he was young when he left

there, Johnny's feelings are deeply bound up with Black

Banner Farm and the possibility of life there as a farmer

if only it can be got back from the War Department.

Mr. and Mrs. Tyler

Mr. Tyler is a tenant farmer who has little

liking for his landlord, Sir Alfred Askew. He and his

wife are kind good neighbours to the Melbury family when

they move into Beckfoot. During his time as a soldier Mr.

Tyler saw much of the world but retains his deep abiding

conviction that there is nowhere like Bannerdale.

Mr. and Mrs. Drake

These two retired actors of the "old

school" live in Gowder End, one of the smaller

villages at the end of a long valley. Their cottage,

which contains a special secret, was inherited from one

of Mrs. Drake's ancestors. They are both appreciative of

Bill and Penny's efforts with the "Black Banner

Players" and regale the young actors with their own

stories of life on the professional stage. Mr. Drake had

his health broken by their special tours during the

second World War and they now live in "genteel"

poverty that arouses both the compassion and the passion

of young Penny

Sir Alfred Askew

Successful in business in India, Sir Alfred

returns to England and purchases a large estate in

Bannerdale. He is both a snob and a petty tyrant. He

attempts to play at being the local squire but does

nothing but build up resentment amongst his tenants and

the other Bannerdale people. Bill and the others have

more than one good reason for disliking this man who

clearly has a large streak of unscrupulousness.

Mr. Morchard

Penny's father is another true lover of the Lake

District and of learning. He is passionate about books

and about preserving the character of the town of

Winthwaite. Bill often wonders how he makes a living in

his old-fashioned but comfortable book-shop. His concern

for his daughter never overcomes his trust in her basic

common sense. For many years she has read books upon his

recommendation and the penetrating accuracy of his

observations and questions have helped to develop her

fine mind and eliminated any sloppy thinking. Mr.

Morchard's own intelligence and his love for Penny are

often masked by an apparent absent-mindedness that

doesn't deceive Bill for very long.

Many Others

There are many other characters to meet but

describing their part in the stories would actually

betray too much of the different plots for those who have

not read all the books. So you must find for yourself

"The Infernal Triangle", Gigi, Carolyn, Paul,

Cracker Crawford and the rather odd Gloria Minworth.

In "Laughter at the Door" Geoffrey Trease

makes this observation:

"Characters I have never taken entire from life,

and, if I have used any particularly recognisable

mannerism, I have felt safer if the story was set in some

remote period…… Perhaps the nearest I came to

it was in Kingsford, the headmaster in the Bannermere

stories, modelled on the craggy, alarming but lovable

history-master, R.S. Bridge, who had loomed so large in

my own schooldays."

In their love of the theatre, of literature and of the

Lakeland countryside it has often struck me that there is

a good deal of Geoffrey Trease in both Bill and Penny. #

(C) Jim Mackenzie 2002

Back to

Collecting Books & Magazines Main Index.

|