| bc | Jane Shaw is a Scottish

author best known for her popular 'Susan' series. Her

other books are more difficult to find and are becoming

much sought after.

[An article in FOLLY number 4, 'Scotland, School and Susan' by Alison Lindsay, helped with the preparation of this short biography.] 'Jane Shaw' was born Jean Bell Shaw Patrick in Glasgow, Scotland, in 1910. Her parents, Dr John Patrick and Margaret, formerly Shaw, both came from large families being each one of ten children, a situation not unusual in Victorian times. Two of Jean's four brothers, William and Henry ('Harry'), were also to become doctors. Robert became an accountant while John graduated from Glasgow University in engineering. Although the family lived only a short distance from Park School, Jean received her early teaching from a governess. She attended the school from 1919 to 1928 and like many other British children's writers, held the position of editor on the school magazine. Jean edited 'The Park Chronicle' during her final two years of schooling before moving up to Glasgow University where she studied arts. Although Jean never actively contributed to the 'Glasgow University Magazine' she did make an appearance or two, being described within as a "...dumpy woman" and having the following remark passed: "This woman's tongue is three inches long but it can kill a man six foot high"! Jean graduated and spent a year in a teacher's training college before deciding that this life wasn't for her. She eventually returned to Scotland after landing a job at Collins, the publishers. Here she began writing, greatly encouraged by the then children's editor, Jocelyn Oliver. Jean married Robert Evans in 1938 and the couple moved to Dulwich in London, living in the topmost of three flats, across the road from the Dulwich Picture Gallery in College Road. During WW2 they were bombed out, living for a time in Bath and later, on a farm in Kent. The family, now with two children, returned to Dulwich. Her husband was offered a job in Johannesburg, South Africa, in 1952 and there they lived until after Robert's retirement in 1978, when they returned to Scotland. Robert died in 1988 and Jane died in 2000. THE BOOKS

British

Girls and Their Adventures Abroad

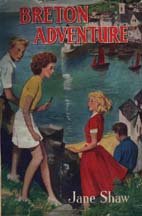

The original novels of world literature, we are told, are picaresque ones. The only plot consists of moving the central character to a new situation and letting new things happen to him. That's how "Lazarillo de Tormes" and the more famous "Don Quijote" started and evolved. So, when we declare that "Breton Adventure", "Bernese Adventure" and "Crooks Tour" have no real plots, we are not intending to denigrate these enjoyable adventures, we are merely defining how each story works. To sustain our interest in this seemingly randomly organised world the author has be especially creative in the way in which she deploys those other two ingredients of successful storytelling : character depiction and the details of style. At first it seems that the

best things come in twos. After all, to complement the

Knight of the Sorrowful Countenance, there is his

ridiculous squire Sancho Panza. Jane Shaw's "Breton

Adventure" presents us with Sara and Caroline, two

cousins who are the complete opposite in personalities.

From the first chapter we are swept along by the sheer

energy of Sara as she begins to struggle with the

situation of being alone in France with no helpful

parents or elder sisters to look after her. She

speculates on her hostess, Whilst Caroline has already considered the situation carefully we are told "Sara was not thinking of anything very consecutively. The thrill and joy of the situation came over her again, and she cried, bouncing up and down a little, "Gosh, Caroline, isn't it marvellous ? We'll have the most gorgeous adventures at last ! Why don't you get more excited ?" "One looney's enough in this party, I should think." Caroline maintained her calm. Inevitably Sara suffers

from "ups and downs" in emotion that make her

depressions and worries almost as exhausting to read

about as her surges of enthusiasm. Caroline is the calm

at the eye of the storm that is Sara. A typical example

of the way the author uses this contrast is a description

of the girls' differing reactions to the house that is to

be their home for several months. In spite of her

feelings of strangeness we are told that "Caroline's

habitual placidity was unruffled." Overcome by

tiredness and homesickness, Sara takes a dive off the

deep end. From this outline it might seem that Caroline is going to find it easier to adapt to life amongst the French. Not a bit of it. Sara's reckless enthusiasm is just what is needed to learn to speak a foreign language whilst Caroline's reserve, and, it has to be admitted, her laziness, both ensure that she never gives up her English accent. Naturally, when you plunge in, as Sara so often does, you often get quickly out of your depth. Thus we have the incident of the artichokes that have to be smuggled in a handkerchief and thrown over a wall, not to mention the day Sara nearly has to sail away into the sunset on a French cruiser.

Having established her two central characters so effectively, Jane Shaw simply has to let the new situations come along at regular intervals. When Sara is lying awake in bed, stricken with both sunburn blisters and hunger, there are two whole pages of fascinating Sara-style dramatic monologue before she decides to venture downstairs in the dark without her glasses. As you would expect, she catches a burglar by flinging a dressing gown over his head and then sitting on top of him. The fact that it turns out to be her host's son and that she has banged his head on the floor in her struggle seems to be of little consequence. Sara seems more concerned over her constant mislaying of her glasses and speculates about getting one of "those what d'you call 'ems on a chain". The idea of an elfin-faced teenage girl with a lorgnette is too much for both Caroline and the reader and the whole episode once again ends in delicious farce. Yet another escapade lies just around the corner. More ridiculous situations, more confusions, more uneasy grapplings with the French language and more tentative encounters with French cuisine, will soon follow. And that's what I mean by picaresque and plotless. It all seems to lead nowhere. True, the end of the book does make use of a typical "treasure" situation, but it is tacked on rather than being a main driver of the overall narrative. Nevertheless, in spite of this seemingly loose structure, certain consistent and important themes do emerge. At first sight the book might seem to be suggesting that foreigners are funny. However, all three books show that there are plenty of kind, helpful, perceptive and attractive people to be found on the continent of Europe. There are also countless episodes where the girls themselves become the ridiculous victims of their own ignorance or insularity. Jane Shaw is even-handed in her distribution of her mockery of the foibles of both the British and the French, and later the Austrians and the Swiss. What emerges above all is a genuine love for the countryside and the people so that at the end the return home is regarded as "that dreadful event" and Sara feels no shame at going "all French" in her display of emotional gratitude to her once feared hostess. If there is a message contained in this book, then it is one of encouraging young people to enjoy the different perspectives that are offered by foreign travel. Plunge in, make an effort, be yourself and you will be rewarded. Of course, there is also the celebration of the instinctive kindness that Caroline in particular shows to her younger cousin. In a scene reminiscent of Jon's treatment of Penny in Malcolm Saville's "Gay Dolphin Adventure", she holds back from the supreme moment of uncovering the "treasure" herself for she knows how much it will mean to her imaginative cousin to be the one that actually stumbles on to the hoard. Her reward for such unselfishness is the pleasure that it gives Sara. The process has been almost imperceptible, but both girls have clearly grown and developed in character without losing the essential contrast in personalities that made them so attractive in the first place. It is less easy to write in detail about "Bernese Adventure" without introducing spoilers, for this later effort has an underlying plot involving the Phillimore diamonds. However, to counter-balance this, the story makes much more use of the idea of the journey, with every new stopping place providing an opportunity for an adventure, mostly totally unconnected with the background mystery. Additional spice is

provided in the relationship between the two cousins by

the introduction of Vanessa (briefly mentioned in

"Breton Adventure"), Caroline's elder sister,

and her husband, John. As the super-calm Caroline has

learned how to take Sara's headstrong excursions into

peril in her stride, so John and Vanessa become essential

to the renewed character interest in this book. Their

status as newly-weds has not yet rubbed off and Vanessa's

conflict of loyalties, as she struggles to satisfy both

her husband and her young charges, brings out another

strong strain of humour. Even more delightfully Vanessa's

grasp of French is worse than Sara's and she claims that

it is no good asking the Belgian garage lady for

"litres" of petrol for "litres" means

"books". Later, when Sara develops a rash,

Vanessa tentatively suggests that they ought to rub some

lotion on it. She remembers the word begins with

"Cam" and, after a little mental tussle, opts

for "Camembert" as the remedy to be applied. The journey to the Bernese Oberland is interesting; their return trip provides non-stop excitement and a very different atmosphere from "Breton Adventure". But we must say no more…. Let us simply note that the canvas of important characters has now extended to four colourful personalities. Last but not least amongst

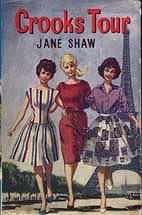

this trio of books is "Crooks Tour" and here we

witness a very different kind of foreign travel. Ricky

and her two friends, Julie and Fay, are the willing

victims of a school trip under the supervision of the

dreaded mistresses. Here the interplay is between the

triangle of central characters who are given very clearly

defined differing personalities. Ricky (real name Erica)

is the adventure-seeker and seems even more preoccupied

with the capture of criminals and spies than the younger

Sara character in the Breton and Bernese stories. Julie

(nicknamed Button) is the manager and organiser, the

practical realist who always tries to discover the ways

and means of completing the foreign holiday with the

minimum of discomfort. Fay is attractively lazy, dreamily

living inside herself and instinctively repelled by the

idea of any unnecessary excitement. She succeeds in

sleeping through the noisiest commotion – even when

Ricky manages to rouse the whole hotel in the middle of

the night by tripping over the practical Julie's washing

line, Fay remains happily in dreamland. Her attitude to

the foreign trip is refreshingly obtuse. In fact Jane Shaw allows

all three girls to be quite satisfyingly against the

whole idea of using French whilst they are abroad. They

gang up to avoid the dreaded Denise Scott, the girl who

has a French grandmother and who is sure to show off her

accent. Whilst in Paris they are happier touring the

shops than visiting the great centres of culture like the

Louvre. They never quite become Philistines but their

enjoyment of Paris is purely unofficial and spontaneous

rather than the predictable following of typical tourist

activities. Ricky's zest for life is brought out by a

series of totally extraordinary events, only one example

of which I will quote here. Left behind once again

because of her confusion over how to board a French bus

and cope with the system of avoiding queues, Ricky

purchases some violets and stands at the edge of the

pavement on the Champs Elysee. Clearly, unlike the classics of world literature quoted at the beginning of this article, there is no darker side to foreign travel that Jane Shaw wishes to touch upon. The deepest emotions explored at any length in these books are those of frustration and embarrassment. The principal attraction of all three stories is the charm exerted by the characters she has created and the skill she has in describing interesting places in just enough depth to make them become intriguing rather than overwhelming. As always, Jane Shaw's gift for dialogue enlivens the most tedious journey and constantly makes her readers imagine themselves safely abroad in amusing and stimulating company. Without doubt, these books are enjoyable to read in themselves, but they are also a splendid preparation for what is the most accomplished work of this author– the Susan stories, where a whole family is brought to life. For, if you look closely at "Breton Adventure", "Bernese Adventure" and "Crooks Tour", you can catch glimpses of the prototypes (or reflections) of the dreamy Midge, the attractive Charlotte, the members of the ghastly Gascoigne household, the practical Bill and even the enthusiastic, kind-hearted, unstoppable Susan. # A

"MUST" for all Jane Shaw collectors The 'Susan' books Now on a separate page. |

bc |