| bc |

IF anybody today remembers Man magazine, it is probably as the slightly risqué girlie mag read - along with Pix and Australasian Post and several other such titles - by the clients of barber shops. Or perhaps as the rude publication that Uncle Ted kept in his toilet, where visiting nephews used to feast their eyes. By the time the magazine died in 1974 it had long been supplanted as a daring girlie mag by more brazen titles and it is hard to describe it in its last years as anything other than a fairly mediocre, middle-of-the-road piece of work, with a mix of soft-porn and male-oriented articles. But that wasn’t always so.

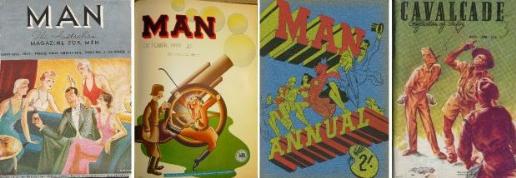

Born in 1936 - the brainchild of ad-man Kenneth Murray - Man prospered against the odds through the tough years of the late 1930s and the second world war to become the centrepiece of an astonishingly successful home-grown Australian publishing empire. In its heyday Man and its spinoffs published excellent fiction and non-fiction articles, cartoons and artwork. Some of the best of Australia’s writers and artists appeared between its covers and many careers were built on its influence. None of this could have been predicted in December 1936, when the first issue of Man was about to appear on Australian newsstands. There is little doubt that Man was strongly influenced by the American magazine Esquire, which had first appeared in 1933, three years before the Australian experiment began. Esquire was enormously successful. Australia and the US were vastly different markets, however, and there were probably many people who doubted that Man could survive. In his 1947 History of Magazine Publishing in Australia, Frank S. Greenop (an employee of KG Murray and a former editor of Man) wrote: “The pretentious and slightly boastful, expensive Man magazine was published by Kenneth G. Murray, a young advertising man of no outstanding literary ability, who was publishing two trade magazines from his Castlereagh St office”. It was printed on heavy art paper with thick, glossy card covers and squared spine. And it sold for the then-suicidal price of two shillings. In its first issue Man boldly declared: “. . . Australia's widely distributed seven millions of population makes producing the real Mackay a tough proposition. But it can be done and MAN will do it. We’re prepared to let the gate money stand over until the goodwill of our name will be worth more than we ever lost.” Greenop wrote: “Despite the hardy gesture of being able to wait for the gate money, the magazine was under-capitalized at the outset and had all the earmarks of being another short-life periodical of good intentions.” But the first issue was a big success. The public seemed to like the plush, art deco style, the high-quality and diverse articles, the risqué cartoons (unusually presented as full-page illustrations) and the titillating photographs by such renowned cameramen as Max Dupain and Laurence Le Guay. Man’s stated policy was to exist on the work of Australian writers and artists, and it had a reputation as a good and prompt payer. After a year it had brightened its presentation, increased its advertising quote and quadrupled its initial circulation (5000 to 20,000). By the onset of the second world war circulation was 60,000 and by 1946 the magazine claimed circulation close to 100,000. Ken Murray clearly knew he was on a good thing and began developing other titles. Man Junior was the first offspring, in 1937. It was a pocket-sized magazine, 96 pages, sold for a shilling and had no advertising. It featured most of the same authors and artists that Man readers were already familiar with.

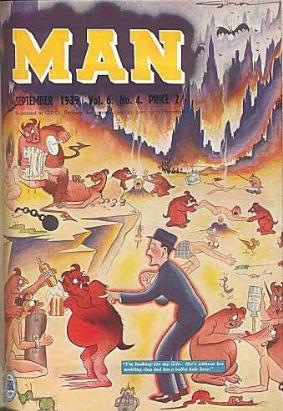

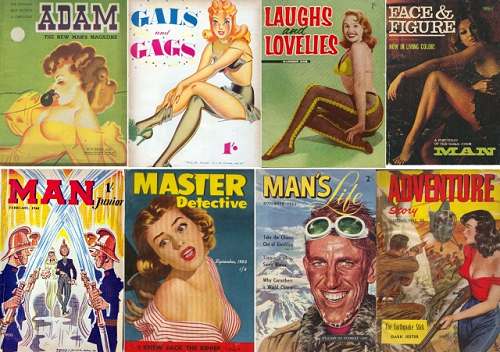

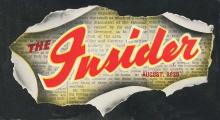

Second off the rank was the short-lived The Insider, a rather pompous attempt at a serious foreign affairs journal. Murray must have sunk considerable resources into The Insider - it’s a quality, well-produced effort - but it seems to have made some embarrassingly inaccurate predictions and assessments and before very long it was absorbed into the more general-focus digest, Cavalcade. Copies of The Insider are virtually impossible to find, but they have great interest due to their war content and the brilliant war illustrations of artists like Jack Gibson, Howard Barron and Clifford Barnes. Digest of Digests appeared in 1938 and prospered due to the fact that many popular foreign digests had become unobtainable in Australia because of the war. The pre-war Man magazine had a strong sense of its own importance and it was unafraid to express strong opinions. Fascinatingly, it ran a powerful pacifist agenda until the very outbreak of the war, urging against war, but also in favour of a policy of armed readiness for Australia. The magazine funded and published a superb series of full-page advertisements pressing the anti-war case. Many of these featured graphic photographs and were really remarkable pieces of propaganda in their own right. One of the most appealing features of Man magazine in the late 1930s (and beyond) was its accomplished stable of artists and cartoonists. The very fine work of people like Jack Gibson, Hardmuth Lahm, Mollie Horsman, Adrienne Parkes, Cliff Barnes, Emile Mercier and several others gave Man and the other Murray magazines a powerful identity. Their good draftsmanship was complemented by Murray’s generally high production values and obvious concern with the best possible paper and printing quality. In 1938 Man pulled off a huge marketing coup, signing up the immensely popular Ion Idriess as editor of a new “Australasiana” section. This generally featured one or two articles by Idriess as well as by many other very well known writers such as JHM Abbott and Frank Clune. Murray tried hard to expand overseas, and was quick to produce a version of Man in England. This was titled The Man, and subtitled, The Empire Magazine for Men. In later years publication continued in England (and America) with the two flagship magazines published as Man Junior and Man Senior. While Man may have been pacifist in editorial tone before the war, the outbreak of hostilities saw the magazine instantly converted into a powerful vehicle for propaganda. In a climate where books, magazines and newspapers were tightly controlled, and where access to paper, ink and other consumables became increasingly uncertain, this was probably an example of sensible pragmatism on the part of Murray. The anti-war advertisements vanished, replaced by astonishingly blatant but beautifully produced propaganda posters which, when more widely recognized, will become valuable collectors’ items. At the same time the magazine was producing superb double-page girlie paintings, mosty done by its female artists and these at their best were as good as anything the fabled Vargas ever did in the USA. The first Man Annual appeared in 1941 and was basically a showcase for the magazine’s cartoons. This formula was followed in the case of Man Junior and these magazines produced annuals until the end of their lives. The war forced the suspension of Man Junior and Cavalcade, leaving only Man and Digest of Digests in business, although Murray also produced a number of one-shot publications - mostly cartoon compilations - as conditions permitted. KG Murray also produced some war-related publications for the Australian Government. Principal among these was Army, an exceptionally fine production by wartime standards, which boasted superb photographs, excellent stories and articles and very good artwork. Proceeds from sales of Army went to the Defence Amenities Fund. South West Pacific was a slightly altered version of Army, printed on better paper, designed to promote Australia's interests overseas - especially in America. It was circulated to influential Americans as part of a bid to promote the importance of continued US spending in the South West Pacific theatre of war, and also to demonstrate how hard Australia was striving to hold up its end of the fight. Murray also published Action, the digest-sized journal of the National Emergency Services. When the war ended, so did Army. South West Pacific continued for a while as a publication of the Department of Information. Man Junior and Cavalcade resumed publication, but The Insider fell by the wayside and it appears the publishers wished it to be forgotten. Adam appeared in 1946 as a pulp magazine of action, sport and adventure stories. The magazine blossomed over time and became noted for its lurid painted covers - many by Phil Belbin and Jack Waugh - featuring semi-naked women in various brands of peril. TRADEMARK CHARACTERS Man's trademark character, the rakish 1890s “gentleman” with a twinkle in his eye, was named Wilbur. He was the invention of cartoonist Hayles, who joined Man from Melbourne. Other Man trademarks included Snifter, a piddling pooch invented by cartoonist Hardmuth (Hotpoint) Lahm. When man tried to ditch the dog early in its life an outcry by readers won him a reprieve. Snifter was so popular he was painted by servicemen on fighting tanks and planes during the war. (This honour was shared by Jack Gibson’s Hell characters, notably Ye Bosse - the head demon). Snifter also featured in a hard-to-find series of small cartoon booklets, some of which were issued with Man and others which were sold separately. TENTH YEAR After its tenth year Man was still able to boast that it had almost exclusively published Australian material. In Man is Ten the magazine's editor wrote that four articles by Winston Churchill, published in 1938, were the only exceptions to this rule. As the 1950s dawned and American girlie magazines flooded the Australian market in huge numbers and at cut-throat prices, Man and its stablemates came under terrible pressure. By then K.G. Murray and Kenmure Press had diversified into an immense range of titles covering an extraordinary range of highly specialized areas of reader interest, ranging from hunting and fishing to motor racing and farming. Man Junior increased in size from its former digest-sized format and was joined by Pocket Man. A series of paperbacks appeared, celebrated the high-quality fiction that was still being published in Man. A nationwide literary prize was launched and the magazine, although by now it was publishing cartoons and articles from overseas (mostly America) the Man stable is still one of the only places a researcher will find home-grown Australian science fiction stories. All during the 1950s Man continued to publish superb artwork. Indeed, the full-colour illustrative pieces by Phil Belbin and Jack Waugh are among the finest that can be found in Australian mainstream magazine publishing.

THE 1950s Also during the 1950s Murray tried to protect its home turf of girlie magazine publishing by bringing out such titles as Gals and Gags, a chirpy little mag full of semi-clad ladies and silly jokes. Other publications (very hard to find) included Man’s Life, Adventure Story and Man’s Master Detective. In 1958 Man followed the lead of some American magazines and produced a calendar featuring paintings of attractive women. This was a success and became an annual feature, though only the first two were painted: the rest were photographed. THE 1960s By the 1960s Man’s formula was starting to appear dated. And although copies were keenly sought in censor-ridden Queensland, its girlie spreads were becoming tame by comparison with other magazines that were pushing the boundaries harder all the time. Man during this period still contains some excellent articles and and photography; more and more content (especially cartoons) was coming from the US. Fortunately Jack Gibson’s Hell retained its traditional price of place: indeed, by the time the magazine folded in 1974, Gibson had produced for Man and its satellites one of the most astonishing bodies of comic and satiric art ever assembled in Australia.

THE FINAL YEARS The 1960s also saw many new magazines issued from the Kenmure offices. Laughs and Lovelies, Face and Figure, Playgirls and Eves from Adam are some of the most noteworthy. In 1969 the traditional painted covers of Man gave way to photographs and as the magazine struggled for circulation in a changing world - censorship gave up the fight and overt pornography was widely available - it tried to go with the flow by publishing more articles about sex and relationships from a male perspective. Perhaps it was ahead of its time in this, but during the early 1970s it looked distinctly off the pace and the magazine folded in 1974. Tragically, much of the publisher’s archives - presumably containing priceless original artworks - were destroyed when the Murray empire was taken over and collapsed. Oddly, although Man was finished, Man annuals kept appearing until about 1977, but these were simply assemblages of nude photographs, giving no hint of the title’s proud heritage. ADDENDUM Former Murray art-room staffer Herbert Young provides an interesting insight into the publishing empire that grew around Man in his 2002 memoir, Sweet and Sour. Young and his colleagues Maurice Cork and Eric Maguire were, amazingly, responsible for most of the art design in the stable's magazines. He noted that freelancers included "Arthur Nichol, Frank Beck, Roy Delgarno, Gerry Lants, Rod Shaw, Hal Missingham, Clem Seale (using the pseudonym Kirkby), Paul Beadle (primarily a sculptor and later head of Newcastle Art College), Tony Hudson, Keith Christie, Dick Sealey, Jack Waugh and Phil Belbin". "The major publications were Man Junior, Man, Adam, Cavalcade, Digest of Digests and eventually Australian House and Garden and Australian Homemaker. All these were monthly periodicals that passed through the art department. It was a heavy workload for the three of us, but also an exceptional opportunity to learn every aspect of the business. We had to do everything from page layouts, lettering, photo retouching and air-brushing, to illustrations for the stories and articles. "Being lowest in the peck order I was assigned the most menial tasks," Young wrote. "This included lettering the name titles directly onto the front cover pictures of the various publications." It also included "air-brushing pubic hairs in photos of nude pin-ups that appeared as a regular feature in Man magazine. Publishing that sort of detail was taboo. "It was no easy task, in retouching, not to have the model look as though she was wearing a steel chastity belt instead of shaven flesh." Even the tame nude photos in Man occasionally caused problems, although the company was allegedly warned of approaching crackdowns and, according to Young, "on those occasions Man magazine was temporarily sanitized to resemble The Catholic Weekly. As soon as the all-clear sounded, naughty bits went back into print and everything reverted to normal. "One instance of panic occurred when Ken Murray was warned that the New Zealand circulation of Man faced a prohibition order because of the inclusion of a particular nude pin-up page. All available staff went en-masse to the printer and physically tore out the offending page from the entire New Zealand edition. Fortunately the backing page consisted only of a full-page cartoon, so no text was lost in the process." COMMENTS |

bc |